By Madhavi P. Patil

Research Fellow, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Northumbria, Newcastle (UK)

By Ashraf M. Salama and Selma Harrington

Co-Directors of the UIA Architectural Education Commission

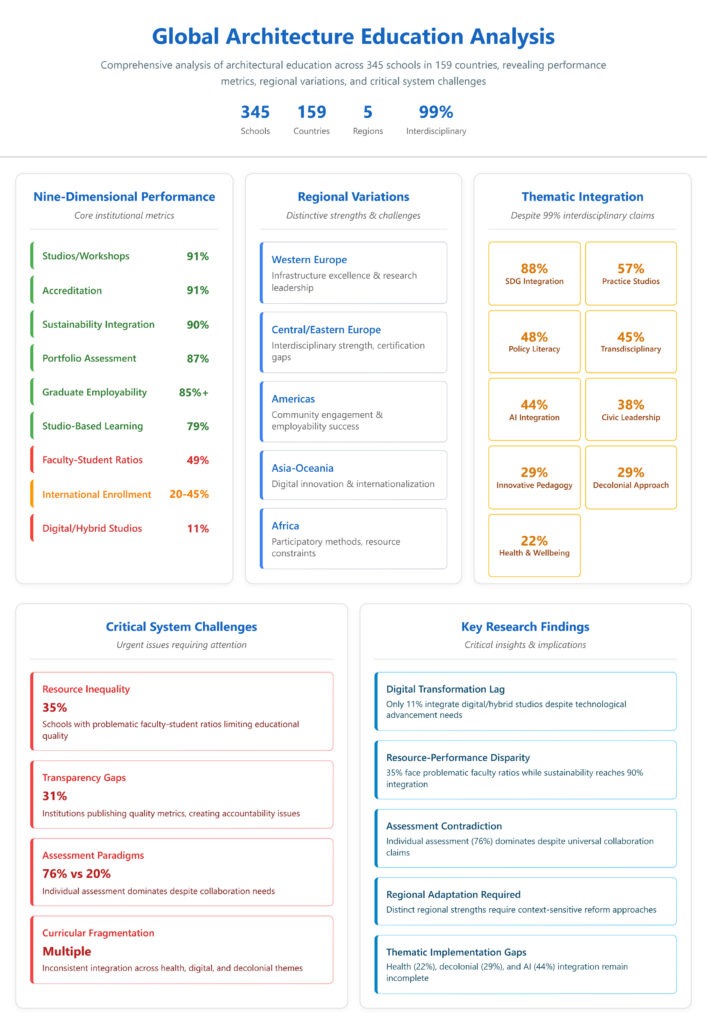

With guidance and support by the UIA President and Board, the UIA Global Survey 2025 was conducted; it is the most comprehensive, data-driven analysis of architectural education yet produced, comprising 345 schools across 159 countries. It provides insights into the evolving landscape of architectural education, including curricula, pedagogy, and professional challenges worldwide. In this essay, we synthesise the key findings, methodologies, regional distinctions, and implications. This includes capturing global trends ranging from health and well-being to decolonial theory, AI integration, and social responsibility.

Architectural education today stands at a critical juncture, where four powerful global forces are converging: climate breakdown, social inequality, digital transformation, and decolonisation. In response, the profession is no longer defined by technical expertise or aesthetic ability; instead, the architect is seen as a civic leader, cultural mediator, facilitator, and interdisciplinary collaborator. The UIA global survey counters these forces and the continuous transition of the role of the architect in society. The survey attempts to examine how schools worldwide are adapting to urgent challenges and identifying the innovations that are emerging in response.

Survey Design and Methodology

To ensure that the findings accurately reflect the global state of architectural education, the survey employed an inductive (pattern-building) methodology. It adopted a two-stage stratified school selection strategy: first, narrowing a pool of 997 globally recognised schools based on official academic rankings and geographical diversity to ensure every region was proportionately represented; then broadening the inclusion of underrepresented areas through accredited open databases. The final dataset included 345 schools, including top-tier, mid-level, and emerging schools, which enabled reliable comparisons across diverse geographical contexts.

Data collection was structured around a multi-dimensional framework, spanning nine areas: curriculum, accreditation, faculty, student outcomes, infrastructure, pedagogy, industry engagement, sustainability, and internationalisation. A thematic analysis addressed ten contemporary concerns, including health and well-being, transdisciplinary teaching, decolonial theory, AI integration, social responsibility, and policy literacy. These frameworks enabled both in-depth analyses and comparative studies across various contexts.

Global Patterns and Divergences

The global survey presents alarming realities in architectural education, depicting a picture that is both challenging and dynamic. Clearly, admission requirements still reflect the old paradigm of architectural education, where academic credentials and standardised test scores take precedence over design aptitude and creative potential, with 79% of schools requiring standardised tests while only 18% require portfolios, a striking contradiction for a fundamentally creative discipline.

While post-pandemic discourse might suggest that virtual studios are adopted widely, the evidence contradicts this narrative. Only 11% of schools have adopted digital or hybrid studio formats, indicating a widespread shift back to traditional models and tools. This gap in digital transformation becomes apparent when juxtaposed with specific regions whose innovation trajectories differ dramatically.

Within this mosaic of pedagogical methods, community-engaged design is another point of regional contrast. Over 50% of programmes have adopted it, but its strongest manifestations are found in America and Africa, which challenge assumptions about where socially conscious pedagogy thrives. Asia, often praised for its dynamism, lags with less than 50% of its institutions integrating community-focused curricula. This geography resists generalisation and shows how local priorities and resources continue to shape pedagogical character. While 78% of schools rely on studio-based learning, the integration varies dramatically: Western Europe leads interdisciplinary approaches at 30% of curricula, yet this drops to just 18% and 22% in Africa and Central/Eastern Europe, respectively.

Assessment practices reveal a discipline rooted in individualistic traditions: group project grading (18%), whereas individual portfolio assessment (87%) dominates nearly everywhere. This suggests that while collaboration and interdisciplinarity are frequently emphasised, there continues to be a strong preference for individual achievement and creative identity.

Faculty-student ratios are significant indicators of educational quality and innovation. The data reveal that over 35% of schools operate above optimal teaching thresholds, which may lead to reduced feedback frequency, weakened interaction with students, and research engagement. For instance, research-intensive universities that nurture innovation often have ratios as low as 1:8. Meanwhile, underfunded schools often have ratios of 1:25 or higher, creating a stratified educational landscape that directly impacts student experience and graduate opportunities.

Student outcomes, such as completion rates and employability, remain high. In America and Asia, leading schools report rates of nearly 98%. International mobility is strongest in Asia and Oceania, indicating infrastructural investments and welcoming policies. Other regions struggle with visa and resource barriers that hinder cross-border exchange. Gender balance is also showing positive movement, especially at the postgraduate level, presenting an opportunity for future inclusivity in the profession.

Infrastructure is widely acknowledged as foundational to hands-on learning, with 90% of schools having dedicated studios and digital fabrication resources. Western Europe and America excel in providing robust research infrastructure, while other regions face intermittent access. Collaborative spaces established in many schools encourage interdisciplinary projects (sustainability, heritage, and urban intervention projects), demonstrating how physical environments can enrich educational practice, not just as a milieu but as active pedagogical agents.

To bridge academia and practice, around 84% of surveyed programmes value external partnerships, and most require internships or co-op placements. Western Europe sets the benchmark with pervasive formal partnerships and robust funding, while Africa and Latin America more frequently rely on development grants and national ministries. Studios focusing on community needs and curricula designed for professional licensure, along with diverse funding sources, ensure that architectural education remains relevant to professional practice in every region.

There is a visible shift toward sustainability and social responsibility. More than 90% of programmes incorporate ecological literacy and climate action, but only about 30% hold formal sustainability certifications. Inclusionary practices, such as co-design, are advancing, albeit inconsistently. Internationalisation, exchange, and language support frameworks are robust in Europe, the Americas, and Oceania. However, the global curricular map still reveals significant gaps. Curricula focusing on multiculturalism are still sporadically treated as electives rather than core elements.

Accreditation remains a global standard, with 92% of schools holding national approvals and many seeking international recognition. However, transparency in publishing data is greatly lacking. Only a third of programmes disclose clear quality/performance metrics. As a result, students and stakeholders must navigate institutional claims without robust comparative data.

Figure 1. Representative selection of architectural education institutions from the UIA Global Survey 2025, illustrating the global reach and diverse geographic contexts of contemporary architectural education.

Regional Contrasts and Innovation Hotspots

Across the UIA’s five regions, the survey unveils a diversity of pedagogical experiments and ambitions but also a striking variation in how each region demonstrates its own distinctive pulse (Figure 2).

Western Europe (Region 1) emerges as the global leader in architectural education infrastructure, sustainability integration, and research excellence, representing 22% of the surveyed schools (75 out of 345). The curricula adopted by European schools successfully blend design principles with heritage preservation and ethical considerations, transforming their studios into living laboratories. Their success reflects their curricular ambition and ability to connect academic work to graduate employability, with 55% of schools maintaining optimal faculty-student ratios of 1:15, setting benchmarks for others to follow.

Central and Eastern Europe (Region 2) demonstrates exceptional strength in interdisciplinary learning and sustainability literacy, comprising 19% of surveyed institutions (64 schools). However, the region faces significant gaps in formal outreach programmes and professional certification processes. While these schools excel at integrating environmental consciousness into core curricula, with 81% following the four- to five-year professional degree model, they struggle with establishing the systematic partnerships and accreditation frameworks that would enhance their global visibility and graduate mobility.

Americas (Region 3) demonstrates a unique model that balances academic research rigour with practical community engagement, representing 19% of the sample (67 schools). This success stems from collaborative education models and licensure-linked curriculum models that directly prepare students for professional practice, resulting in greater employability. North American schools have pioneered integrated pathways that combine theoretical depth with hands-on experience, with 78% offering four- to five-year degrees, while Latin American institutions increasingly focus on locally responsive design solutions, despite facing challenges in data transparency.

Figure 2. Comprehensive Analysis of the Global Architectural Education Landscape

Asia and Oceania (Region 4) lead global architectural education in digital innovation, internationalisation strategies, and the implementation of sustainable campus design, constituting 24% of surveyed schools (84 institutions). These regions have successfully integrated indigenous knowledge systems and co-design methodologies into mainstream curricula, creating pedagogical models that strike a balance between technological advancement and cultural sensitivity. Schools in Australia, Singapore, and China excel particularly in attracting international students while maintaining strong connections to local design traditions and environmental considerations, with 75% adhering to the four- to five-year professional degree standard.

Africa (Region 5) demonstrates remarkable resilience and innovation in social equity through participatory design methods and strategic local partnerships, representing 16% of the surveyed institutions (55 schools). Schools have developed distinctive approaches to community-centred architectural education, often leveraging relationships with government ministries, professional councils, and development agencies to create impactful field experiences. However, persistent resource gaps and inconsistent data reporting significantly limit the global recognition and systematic analysis of their pedagogical innovations, with only 15% maintaining optimal faculty-student ratios of 1:10.

Challenges and Future Trajectories for Reimagining Architectural Education

Despite some global convergence in sustainability and digital integration, architectural education faces five critical gaps that undermine its potential:

- Resource inequality, where funding disparities create cascading effects from faculty and teaching staff deficits to limited research capacity, with 35% of schools operating above optimal faculty-student ratios directly impacting studio quality, while only 15% achieve optimal conditions.

- Inconsistent internationalisation and transparency, with dramatic regional variations where Asia-Oceania achieves 20-45% international student enrolment while Africa and parts of Europe maintain only 1-13%, compounded by only 31% of schools disclosing clear quality indicators.

- Fragmented curricular development, where diverse regional innovations from AI-enhanced studios to community-embedded projects enhance local adaptability but create significant content gaps, with health-focused design in only 22% of schools and decolonial practices in just 29%.

- Persistence of outdated educational paradigms that continue to prioritise individual achievement over collaborative design approaches, with 76% relying on individual portfolios versus only 20% using group project grading, failing to integrate socially responsive design thinking.

- Thematic integration disparities revealed through the survey’s analysis, where despite 99% adopting interdisciplinary collaboration, only 38% address architects as policy makers, 29% incorporate innovative pedagogical models, and 22% focus on health and well-being in design.

These challenges require innovative solutions that maintain contextual responsiveness while establishing stronger global frameworks for collaboration, resource sharing, and quality assurance.

The UIA Global Survey 2025 reveals that architectural education is at a defining moment, where persistent challenges coexist with remarkable innovation. While the survey exposes critical gaps in resource distribution, curricular development, and pedagogical approaches, it also demonstrates the discipline’s inherent capacity for transformation. Schools worldwide are successfully pioneering community-engaged studios, integrating emerging technologies, and maintaining strong connections between academic learning and professional practice. This dual reality of both limitation and possibility positions architectural education not as a system in crisis, but as one ready for strategic evolution.

The path forward demands decisive action from educators, policymakers, and professional bodies who must move beyond incremental adjustments toward systematic change. This survey provides the evidence base for targeted investment in faculty development, transparent quality assurance, and expanded access to critical competencies that prepare graduates for complex global challenges. The future of architecture depends on educational institutions that can strike a balance between local responsiveness and international collaboration, preserve disciplinary identity while embracing interdisciplinary thinking, and maintain creative excellence while addressing urgent societal needs. The architects of tomorrow require nothing less than educational systems that are as adaptive, innovative, and forward-thinking as the challenges they will face. This survey is a call to action: to reimagine who architects are, what they need to know, how they are taught, how they learn, and what roles they are prepared to serve in a world of complex, urgent change.