By Bartosz Dendura

Member of the UIA Sustainability Commission

This article analyzes the latest reports from the Central Statistical Office, showing how construction trends are changing in Poland.

“Eco” often loses to “cheap”—especially when the market slows down and everyone becomes more cautious. Poland’s 2024 construction stats show a clear cooldown: fewer completed homes and declines in non-residential completions as well. In this kind of climate, clients and investors double down on cost control and avoid anything that feels uncertain. And that’s exactly how many people still see “green” materials: more expensive, harder to judge, and sometimes suspiciously marketing-driven. This article connects those dots and makes a simple case: decarbonisation won’t scale on slogans alone. It scales when low-carbon options win on total value—performance, durability, warranties, and financing—so “eco” stops feeling like a premium lifestyle choice and starts looking like the safest, smartest default.

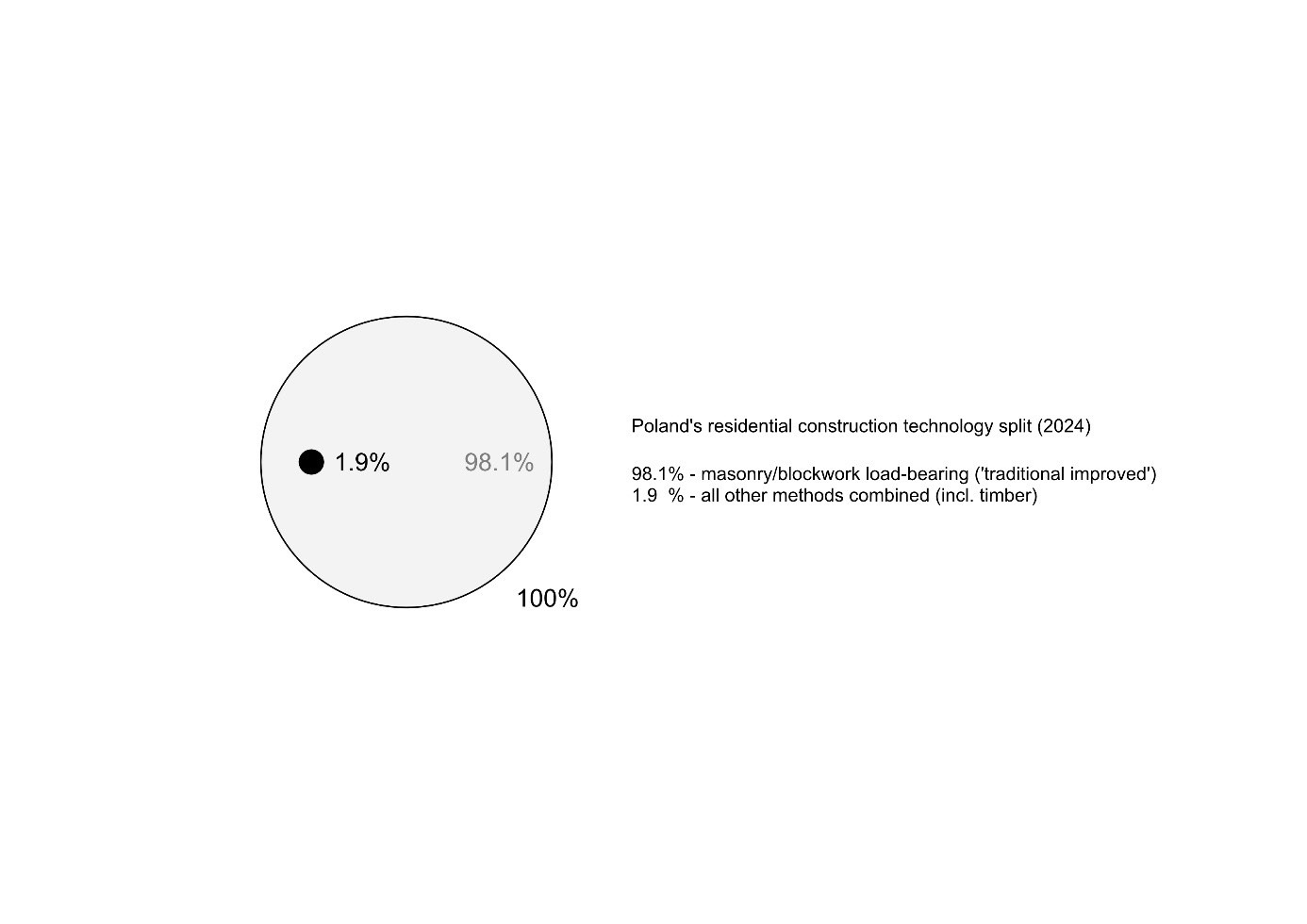

Poland is a European growth story—rising incomes, rising expectations, and a housing market that has expanded fast. Yet the way we build homes remains stubbornly unchanged. The Central Statistical Office (GUS) does not publish CO₂e figures for new housing in its annual construction reports, so in this article I use the EP energy-performance index as the closest official proxy for operational demand. But the most telling signal sits elsewhere: technology lock-in. Across 2020–2024, “traditional improved” masonry construction accounted for roughly 98% of all new residential buildings; in 2024 it was 98.1%. That leaves just 1.9% for everything else combined—monolithic concrete, large-panel systems, steel and timber. And when the market cools, “eco” tends to lose to “cheap”: Poland completed 99.1 thousand new residential buildings in 2023 and 88.2 thousand in 2024. As a practising architect and academic researching sustainable housing behaviors, I read these numbers as a question of risk and trust: what would need to change for low-carbon construction to stop feeling like a premium experiment and become the safest default?

The slowdown test: what Poland built in 2020–2024—and why it matters

If you want to measure the real pace of decarbonisation in housing, begin with what is easiest to verify: the number of homes the country delivers, and the dominant type of building. The five most recent annual GUS reports (2020–2024) show a market that has been expanding in ambition—bigger expectations, bigger programmes—yet remains structurally conservative in its built output.

In Poland, new residential construction is overwhelmingly shaped by single-family homes. Across 2020–2024, detached buildings consistently represent around 97% of all newly completed residential buildings. This dominance is not accidental. For many households, the single-family house is still the clearest expression of upward mobility: more space, a garden, privacy, and control over one’s environment. Practical drivers reinforce the dream—smaller, simpler houses (including semi-detached or single-storey forms) can be built at predictable cost, and land remains available on the edges of cities.

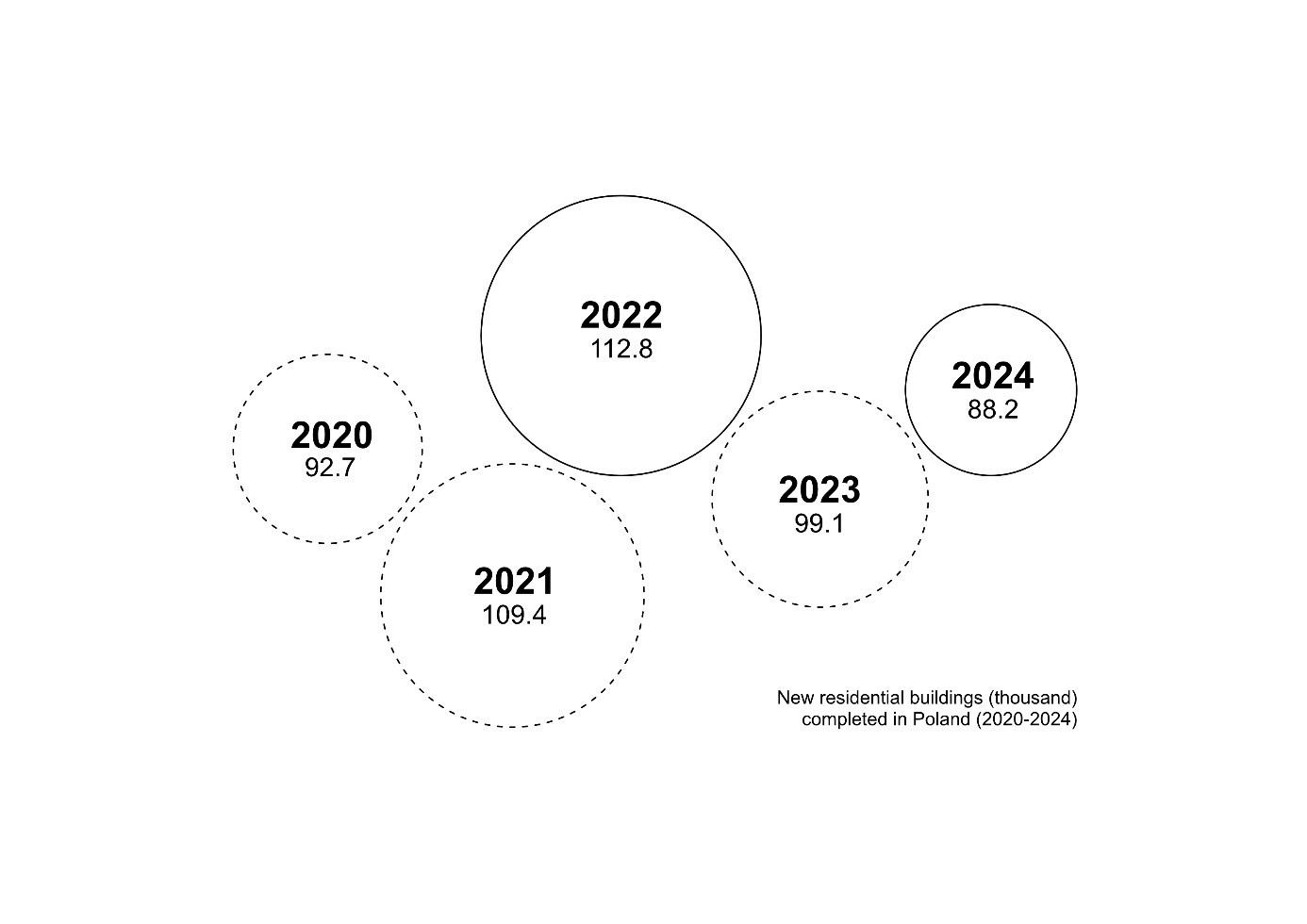

But the same structure that makes the market scalable also makes it cautious. In absolute numbers, Poland completed 92.7 thousand new residential buildings in 2020, 109.4 thousand in 2021, and 112.8 thousand in 2022. Then the cycle turned: 99.1 thousand in 2023 and 88.2 thousand in 2024—two consecutive years of decline and the lowest level in this five-year window. In a cooling market, investors and private clients do what markets reliably do: they avoid uncertainty, tighten specifications, and prioritise solutions that are easiest to price, insure, and deliver.

This is the context in which “eco” most often loses to “cheap”—because “cheap” is frequently shorthand for “known.” When most housing is delivered by small contractors in a fragmented single-family ecosystem, the default is not only a material choice; it is a risk-management strategy.

Good news in EP—yet still not a carbon metric

Before we talk about decarbonisation, one uncomfortable fact has to be stated clearly: GUS housing reports do not provide CO₂e for new residential buildings. What they do provide—and what policymakers and designers in Poland routinely operate with—is the EP indicator: annual demand for non-renewable primary energy for heating, ventilation, cooling, and domestic hot water in a new residential building.

On paper, the direction is positive. Over the last five years the average EP value for new residential buildings fell from 91.3 to 73.2 kWh/(m²·year) (with similar reductions reported for single-family and multi-family buildings).

This is the part of the story Poland can be proud of: better envelopes, better standards, a real shift in energy performance.

But EP is still only a proxy. It does not automatically translate into low operational emissions, because emissions depend on how energy is produced and what systems are installed. Here, GUS data gives a sobering snapshot of the “default” technical choices in new housing: in 2024, 37.1% of newly completed dwellings had district heating, while the rest relied on individual systems—and among those, gas boilers dominate (with a persistent, non-negligible share of solid-fuel systems visible across 2021–2024).

This aligns with what life-cycle assessments keep showing in practice-led research: in a typical Polish single-family NZEB, the use phase (B6) can outweigh the embodied impacts (A1–A3) by a “few times”—so material upgrades alone won’t rescue the climate balance if operational energy stays carbon-intensive.

The architectural takeaway is pragmatic: decarbonisation scales when the building’s energy concept is reliable. Today that means no gas by default, a properly sized heat pump matched to the plot (ground-source where feasible, air-source where not) paired with PV, and moving away from EPS toward mineral wool and preferably wood-fibre insulation. The risk is execution: undersized grids, oversized heat pumps, and PV export limits can turn “green” into a bad user experience—pushing clients back to familiar gas or pellets.

Kraków is the reminder that change can become normal quickly: a clear rule—such as the city-wide ban on burning solid fuels introduced in September 2019—made cleaner air a tangible, everyday benefit.

Why “Eco” Still Loses to “Cheap”: what clients actually buy is certainty

When clients say “cheap”, they rarely mean the lowest number in a spreadsheet. They mean certainty: a system that thousands of buildings have already proven, a contractor who can fix mistakes on instinct, a structure that won’t raise questions at the kitchen table—or in the sales office.

This is why the GUS number hits so hard. In 2024, 98.1% of new residential buildings in Poland were erected in the “traditional improved” method—masonry/blockwork load-bearing. Everything else combined—monolithic, large-panel, steel and timber—adds up to 1.9%.

This is not a technology choice; it is a cultural default.

Timber loses to that default through three predictable doors.

The first door is price. In single-family projects, structural timber commonly lands at about +15% at developer’s standard, and the structure is the cost driver. When budgets tighten, a premium that appears immediately will almost always beat a benefit that arrives later. “Eco” becomes an optional upgrade—like a better finish—rather than a foundation of the design.

The second door is fear dressed up as “common sense”. I still hear the same myths: it will be damp, it will smell, it will squeak, it won’t last. These fears grow when the market’s most visible “timber” offer is not contemporary architecture, but a tired stereotype—catalogue manor houses, generic forms, weak detailing, sometimes even poorly dried wood. Bad examples teach faster than good ones.

The third door is sellability. In my Kraków office we studied a 25-unit, 1,200 m² infill building where timber could have reduced disruption and shortened the time we would occupy a busy street corridor. The idea died not in engineering, but in marketing: agents warned the investor that buyers would hesitate. The sentence was simple: “I wanted timber, but I won’t sell it.”

The paradox is painful: “eco” is often more expensive, yet premium clients—who could afford it—avoid it precisely because there are too few premium references. The way out is equally simple: education through visible proof. When people can tour a contemporary timber building, hear a user “success story”, and see awards attached to real architecture (as with our D13 Wooden House), “eco” stops being a risk and starts becoming the new normal.

Conclusion

Poland’s housing statistics tell a story that many countries will recognise: progress is real, but uneven. Energy performance indicators improve, standards rise, and public awareness grows—yet construction technology remains almost unchanged, locked into masonry/blockwork load-bearing as the “safe default”.

This is why “eco” still loses to “cheap”: not because people reject sustainability, but because they reject uncertainty.

Kraków offers a useful analogy. For years the city was a black spot on air-quality maps; once clear rules and consistent implementation arrived, cleaner air became an everyday experience rather than a promise. A similar shift is possible in housing—when low-carbon choices become easy to trust, easy to execute, and easy to explain.

The lever I would bet on is education, supported by a gradual removal of the worst options from the market. If we want decarbonisation to scale, we must make the better choice feel normal: visible examples, competent teams, honest performance data, and architecture that proves “eco” can also be desirable.

Keywords: Sustainable Housing, Timber Architecture, Decarbonisation, Construction Economics, Technology Lock-in.